Ella Fitzgerald, Dinah Washington, Helen Humes, Billie Holiday, Ivie Anderson, Helen Ward, Helen Forrest – these are some of the iconic big band vocalist names whose works have inspired performances at Lindy Focus and, for Fitzgerald and Washington, featured charts in the Heritage Sounds transcription projects. As we approach the year of Erskine Hawkins as the featured bandleader for the 2024 transcription project, you may notice that there’s not a definitive vocalist in his lineup, except perhaps Hawk himself yelling out “Tuxedo!” as his band launches into that famous tune. His discography hints at 11 featured vocalists and there were others as the band continued live performances into the 1960s. The in-depth biographies of most these musicians may be largely lost to time, but here’s a bit of information – dates denote recording release years and/or other dates I may have found online:

JIMMY MITCHELL, alto saxophone and vocals (1936-1949 recordings, ‘Bama State Collegians and E.H. Orchestra)

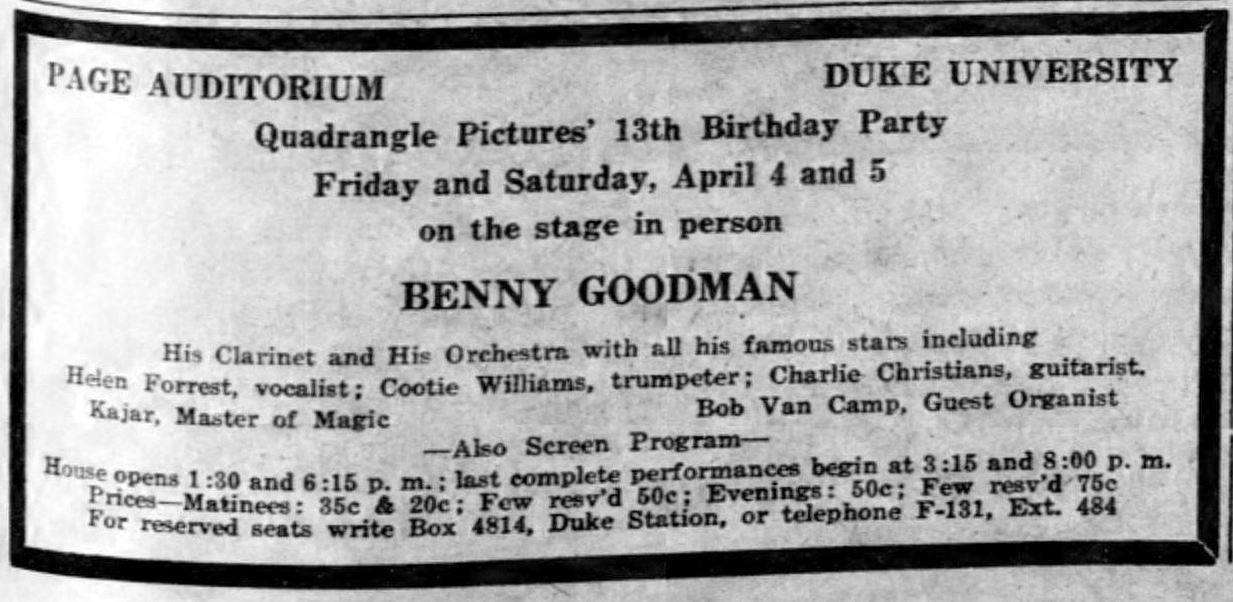

“Hawk, if you can keep us working, we will stay with you.” This was the sentiment that the rest of the ‘Bama State Collegians as the band embarked on their tour to New York in 1934. Jimmy Mitchell was one of those musicians, a reed player and the most consistent and prolific vocalist of the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra. Mitchell goes all the way back to Birmingham Industrial High School and, as a student of the esteemed “Fess” Whatley, was granted a music scholarship to Alabama State Teachers College along with others of his Industrial HS peers, including Erskine Hawkins. There is scant biographical information about Mitchell online, but one thread throughout is that mentions of Mitchell in the press and in references online show that he was a featured vocalist, a named musician in advertisements, and thus a draw to the orchestra for his popular vocal stylings.

Mitchell recorded 39+ vocal sides with the Orchestra, in addition to being featured on radio broadcasts, for which we still have recordings. The ‘Bama State Collegians were signed to Vocation and Mitchell recorded the first song of their first New York recording session, “It Was a Sad Night in Harlem” (an ironic choice, as I’m certain their residency at the Savoy inspired many happy nights) on July 20, 1936. For the transcription project, we’ve picked his rendition of Keep Cool, Fool from 1941. His last recording with the Orchestra was “Brown Baby Blues” on November 30, 1949.

WILLIAM “BILLY” BOONE DANIELS (1935-1936)

Billy Daniels is one of most famous people on this list and has a Hollywood walk of fame star to prove it. Born in Jacksonville, Florida, Daniels moved to Harlem in 1935 with the intention of attending law school at Columbia. He worked at Dickie Welles’ Place as a busboy, then as a singing waiter. It was here that Daniels was plucked from obscurity by Hawkins and invited to join his orchestra. He toured with the Hawkins orchestra throughout 1936 and recorded three sides with the band. He left the band to pursue his solo act, with performances at the Onyx Club, Ebony Club and the Famous Door.

This was just the beginning – Daniels went on to radio, records, Broadway productions, Las Vegas residencies, made three films for Columbia Pictures, and hosted his own television show starting in 1952. The Billy Daniels Show was the first sponsored television show starring a black entertainer. The show was broadcast from the same theater that would later be named the Ed Sullivan Theater, now home to The Late Show with Stephen Colbert.

His most famous tune was “That Old Black Magic,” recorded in 1948, after his service in the Merchant Marines during WWII ended, and sold more than nine million copies. Compare to his first recording ever (which was during the first Hawkins orchestra recording session in 1936), the classic “Until the Real Thing Comes Along.”

MERLE TURNER (recordings from 1936-1938, ‘Bama State Collegians and E.H. Orchestra)

Merle Turner from Charleston, West Virginia joined New Orleans-born, Texas-based territory bandleader Don Albert as a vocalist in 1935. The band recorded 8 sides at a recording session in San Antonio, Texas in November of 1936, including a Turner vocal on “Sheik of Araby” (with the “with no pants on” call/response).

In June of 1937, Albert’s orchestra arrived in New York, but had difficulty finding work in a saturated market. They played at least one show in New York, because Leonard Feather wrote in Melody Maker about the band’s recording of Sheik, which had “caused a considerable mystery” since they were an unknown band.

Turner (perhaps seeing the writing on the wall, needing work, and/or using the review of his vocal recording as a springboard) left the Albert band that same month to join the ‘Bama State Collegians. Wasting no time, Turner went into the studio with the Collegians on August 12, 1937, singing “I’ll Get Along Somehow,” with the croon of an Ink Spot and a high note to finish. Turner recorded several more sides with the Orchestra through September of 1938.

Beyond 1938, I was only able to locate a recording Turner made in 1946 with Hawkins alum/trumpeter Wilbur “Dud” Bascomb leading the session, the aptly titled “Just One More Chance.”

RUBY HILL (1937)

While Hill is credited as being a regular vocalist with the Hawkins Orchestra in 1937, her web presence is primarily limited to her performances at the Harlem Uproar House and the Apollo Theater.

On January 29 1937, Hill appeared at the Apollo along with Willie Bryant and comedian Pigmeat (presumably Markham? A Durham, NC native!).

In the April 1937 issue of The Show-Down, a magazine documenting night clubs, theaters, and performers, gave Ruby Hill a shoutout – “Ruby Hill’s torch songs touch one from head to toe” – in a rundown of accolades from a revue at the Harlem Uproar House. The revue featured Hawkins’ Orchestra and a cast that included vocalist Velma Middleton, Savoy Ballroom emcee Bardu Ali, and Tiny Bunch leading a troupe of Lindy Hoppers.

On November 3, 1939, Hill was back at the Apollo Theater with Noble Sissle.

I was not able to locate a photograph of Hill, so I leave you with a photograph of the chorus line at the Harlem Uproar House from 1937.

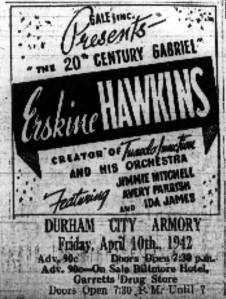

IDA JAMES (recordings 1938-1939)

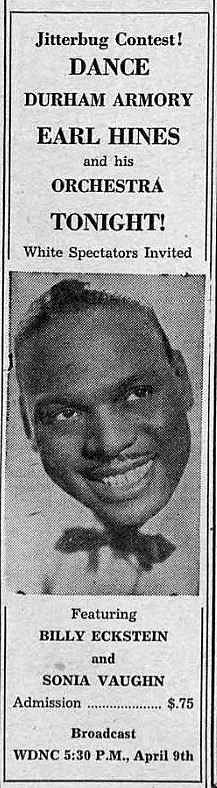

A native of Providence, Rhode Island, Ida was still young when she started her career in Philadelphia, performing on The Horn and Hardart Children’s Hour on WCAU in the 1930s. By January 1937, she was singing with Earl Hines’s Orchestra in Chicago and stayed with him until May 1938, when she joined the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra. She stayed with the Orchestra on and off until 1942, which was basically a launch pad for her, because she stayed busy in the 1940s!

- 1944

- Recorded two soundies with the King Cole trio in 1944, “Who’s Been Eating My Porridge?” and “Is You Is, or Is You Ain’t My Baby?”

- Appeared in the Republic Pictures musical Trocadero, performing “Shoo Shoo Baby”

- A residency at Cafe Society in New York

- Recorded two more soundies, “His Rockin’ Horse Ran Away” and “Can’t See for Lookin’”

- 1945

- Appeared in Olsen and Johnson’s (the creators of Hellzapoppin’) Laffing Room Only revue

- Appeared in the all-black musical Memphis Bound

- Recorded two sides with the Ellis Larkins Trio

- Ended the year with her own USO unit and went to the South Pacific

- 1946

- Toured the theater and nightclub circuit in the US

- 1947

- Began a residency at the Savannah Club in New York that lasted over 6 months

- Starred in the film Hi De Ho as Cab Calloway’s manager

- Signed with the Manor label, but only recorded 4 sides before the recording ban of 1948

- 1949

- Appeared on the TV show Adventures in Jazz

James continued recording and performing in theater until the mid-1950s. For the transcription project, James gives us three vocal tunes: Knock Me a Kiss, I the Living I, and Jumpin’ in a Julep Joint.

DOLORES BROWN (recordings 1939-1940, 1945)

Brooklyn native Dolores Brown was born to musical parents – Edna Hiddleston, a pianist, and Bill Brown, trombonist and leader of Bill Brown and his Brownies, who had a radio broadcast and cut a few sides for Brunswick in the late 1920s. Brown cut her teeth performing at school and community functions as a tween and transitioned to professional work in her late teens.

In 1938, Brown had a residency at the Black Cat in Greenwich Village as part of the club’s revue. She performed at the Apollo Theater’s Amateur Night and, like the Cinderella story of Ella Fitzgerald, was scouted and joined Duke Ellington’s Orchestra in the summer of 1938. She toured with Ellington until January, 1939, then left the Orchestra for reasons unknown. She joined a revue at the Kit Kat Club for spring of 1939.

On August 17, 1939, the California Eagle reported that Brown had joined the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra. Brown was featured in several recording sessions in 1939 and 1940, starting with the recording Rehearsal in Love. She was also featured at times with the Savoy Sultans during the Hawkins Orchestra’s Savoy Ballroom residency.

Unfortunately, Brown’s early newspaper mentions focus on her relationship with cornet player Leslie “Bub” “Bubber” Lewis, who she started dating in 1936, so we don’t get a lot of context about what she was doing at the time. In 1940, Brown ditched Lewis and fell in love with (and ultimately married) one of the Orchestra’s trumpet players, Marcellus Green. Following their marriage on December 2, 1940, Brown left the band and Hawkins re-signed Ida James as the Orchestra’s female vocalist. Just before she left, Brown recorded the apropos S’posin’ on November 20, 1940, one of the songs selected for the transcription project.

In August of 1942, Green and other Orchestra members Avery Parrish, Lee Stanfield, and Heywood Henry were in a terrible automobile accident near Chattanooga, Tennessee that killed Green and injured the others. I can’t even imagine how significantly this impacted such a closely-knit group, not to mention the accident occurring less than two years into Brown’s marriage to Green.

Brown was all over the jazz-sphere in 1943, at nightclubs and theaters in Pittsburgh, Allentown, Boston, Montreal, Chicago, Detroit, and back to New York. Brown joined Don Redmon’s Orchestra from January through August of 1944, then appeared at the Onyx Club until November of that year. She did a brief stint with Lucky Millinder in 1945, then went back to the Hawkins Orchestra!

The August 4, 1945 issue of Afro-American commented on “her courageous return to show business. Dolores thought that she was through with singing, but fate played a different hand.” She stayed with the Orchestra until April of 1946, then left again for reasons unknown. She continued recording and touring throughout the US with jazz luminaries through the 1960s. Brown never remarried and news of her passing in 2003 named her as “Dolores Green.”

EFFIE SMITH (1944 Jubilee Broadcasts)

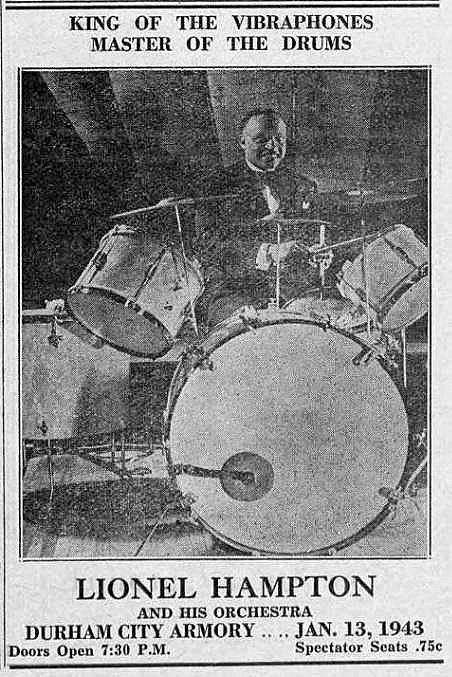

From an Amazon.com record description: “Part of the explosion of black entertainment that occured on the West Coast in the early 1940’s, which led to an eruption of independent record labels and the birth of the R&B record industry, California was the breeding ground for the recording careers for a host of strong, talented women performers – among them was Effie Smith, a talented singer and comedienne whose career stretched from the early 1930’s until the early 1970’s. Early on Effie worked in Lionel Hampton, Erskine Hawkins and Benny Carter’s orchestras, and later on with small bands organized by Johnny Otis and her husband, John Criner, as well as R&B legends Roy Milton and Buddy Harper. With the advent of rock n’ roll in the mid-fifties, Effie made several records with The Squires for the Los Angeles based Vita Records imprint.”

Smith was marketed as Hawkins’ featuring vocalist, as you can see from this head shot, noting Gale Agency as her manager. The only two recordings we have of Smith with the Hawkins Orchestra are those from the October 1944 Jubilee Broadcasts, which were only available on CD until I uploaded Straighten Up and Fly Right to YouTube contemporaneously with the writing of this blog post. Enjoy this recording now and the arrangement live at Lindy Focus once we’ve completed the transcription project.

ASA “ACE” HARRIS, piano and vocals (recordings 1944-1950)

Harris grew up in Florida playing piano and in 1930 (when he was 20) he joined Billy Steward’s Celery City Serenaders (Celery City = Sanford, FL), a territory band that toured throughout most of the US. In 1935, he joined the Sunset Royal Serenaders. Within months of joining the SRS, their frontman Steve Washington died of pneumonia in January of 1936. The trombonist Doc Wheeler took over leading the band and, during a double bill with the Tommy Dorsey Orchestra in Philadelphia, Dorsey snaked the band’s 4/4 version of Marie with band vocals (originally an Irving Berlin waltz) and it became a hit for Dorsey in 1937. After proving himself as an excellent showman, Harris took over leadership of the band and they recorded in 1937 as Ace Harris & his Sunset Royal Orchestra.

When the band made it to New York City in 1939, Harris decided he wanted to stay. From 1940-1942, Harris was an accompanist and arranger for The Ink Spots. The Ink Spots often toured with the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra, so it was easy for Harris to transition to performing with the Orchestra full-time in 1944. The Orchestra had a hit in 1945 with his recording of “Caldonia” (#13 for the year on R&B charts). He continued to simultaneously perform with the Orchestra and manage his own solo recording career, recording for New York City labels Hub and Sterling between 1945 and 1948. In 1947 he left the Orchestra, but returned from 1950-1951 and recorded the Orchestra’s last R&B hit (#6 on the charts in December 1950) “Tennessee Waltz.” He also returned in 1955 to record a couple of singles for Decca.

Throughout the 1950s Harris continued performing and recording. He had a residency at Chicago’s Black Orchid alternating and performing piano duos with Buddy Charles. The pair had such a following that they recorded an album in 1957.

At some point, Harris’ sister married Hawkins, but it is not clear if that was Hawkins’ first wife Florence Browning, who he married in 1935, or if it was Gloria Dumas, who he married “later,” of whom the internet has almost no information.

Harris’ daughter, whose name is also Asa Harris, is/was a Chicago-based jazz vocalist.

CAROL TUCKER (recordings 1945)

Tucker grew up in Chicago in a musical family, as the child of a bandmaster of the Eighth Illinois Regiment. She attended DuSable High School, where she worked with Walter Dyett, a music educator who also worked with young Nat King Cole, Bo Diddley, Milt Hinton, and Dinah Washington. After graduating in January 1945, she secured an audition and landed a spot with the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra. The Orchestra had a residency at the Regal Theater, then hit the road to cities on the east coast. The press was receptive and, by the time she got to New York with the band, her star had risen.

She recorded two tunes with the Orchestra, “I Hope I Die If I Told You A Lie” on March 28, 1945 and “Prove It By the Things You Do” on April 23, 1945 (the B side to Harris’ “Caldonia”).

At some point while in New York, Tucker became “stricken” with an unidentified ailment. Hawkins’ physician examined Tucker and recommended that she return to Chicago to rest at home. She died of this mystery illness in the first part of March 1946.

RUTH CHRISTIAN (recording 1946)

Christian grew up in New York and showed up in the entertainment press in 1939 as the vocalist for Buddy Walker and His Harlem Varieties. She had radio performances and was billed as such in a star-studded opening performance at the Community Theater Of St. Martin’s in Harlem on October 11, 1940, along with Ethel Waters, Katherine Dunham, Willie Bryant, W.C. Handy, and the Delta Rhythm Boys, among others.

At some point, Christian attended and graduated from college, perhaps in this gap between press clippings in the early 1940s. While in college, Christian met Ethel Harper, Leona Hemingway, and Charles Ford, who began singing as a vocal quartet, sharing performances with college choirs and participating in church services. The quartet began singing professionally around 1942, billing themselves as The Ginger Snaps (but may also be identified as the Four Ginger Snaps, the Gingersnaps, and the Four Gingersnaps because news sources seem to have chronic issue with band names). Their first show of record is as part of “Harlem Cavalcade”, an all-black variety show produced by Ed Sullivan that ran for most of May 1942 at the Ritz Theater. In July 1942 they appeared at Kelly’s Stable, then at the Apollo Theater the second week in November, sharing the stage with the Fletcher Henderson Orchestra and Jackie Mabley (later “Moms” Mabley). After a brief run in Philadelphia, they were back in New York and on the radio in December 1942 and at Le Ruban Bleu in January and February 1943, then back to Philly in April to appear with Sidney Bechet in March and April 1943. They spent the summer of 1943 performing in Wildwood, NJ, then back to Philly, then to Cleveland, St. Louis, Wilkes-Barre, and more.

Before the summer gig in New Jersey, The Ginger Snaps filmed three soundies in New York – “Keep Smiling“, “Wham,” and “When Johnny Comes Marching Home.”

In 1944 they appeared on the G. I. Journal radio show, produced by Armed Forces Radio Service (AFRS), singing what appears to be their signature or perhaps most popular song, “The Shrimp Man.”

On April 21, 1944, the Ginger Snaps were back at the Apollo, this time with the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra, and now we know for sure that their paths crossed. The rest of 1944 was back on the road to (you guessed it) Philadelphia, they appeared in a Royal Crown Cola ad, then performed in Atlantic City, Buffalo, Baltimore, Philly, Pittsburgh, Detroit, Rochester, then to California in 1945! In 1945 they recorded songs for three different entities while in Hollywood – at NBC Studios in Hollywood for the AFRS Jubilee series, for University Records, and RCA.

In early 1946, Christian left The Ginger Snaps to join the Hawkins Orchestra. She recorded one side with the Orchestra on April 24, 1946, “That Wonderful Worrisome Feeling.” Unfortunately, Christian then disappears from online sources. POOF!

COZINE STEWART (recording 1946)

The only mentions of Stewart online is her live performance with the Orchestra, a radio broadcast from the Hotel Lincoln’s Blue Room, New York, May 1, 1946 – the song is Personality and I could only find it on CD or LP. I’d like to think someone with the name Cozine has a wonderful personality.

LAURA WASHINGTON (recordings 1946-1947)

Birmingham-born Washington started singing as a child, performing in small clubs and churches, where she was scouted by Birmingham jazz musician J.L. Lowe. Lowe later recommended Washington to Hawkins and she joined the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra in New York as a teenager in 1946 (apparently beating out hundreds of interested vocalists, per the news caption at right), making her debut at the Strand Theater on Broadway. She recorded a total of 5 songs with the Orchestra, scoring a hit within a few months with the tune “I’ve Got a Right to Cry.” The song reached #2 on the Billboard “race” charts and #17 in the year-end ranking for 1946.

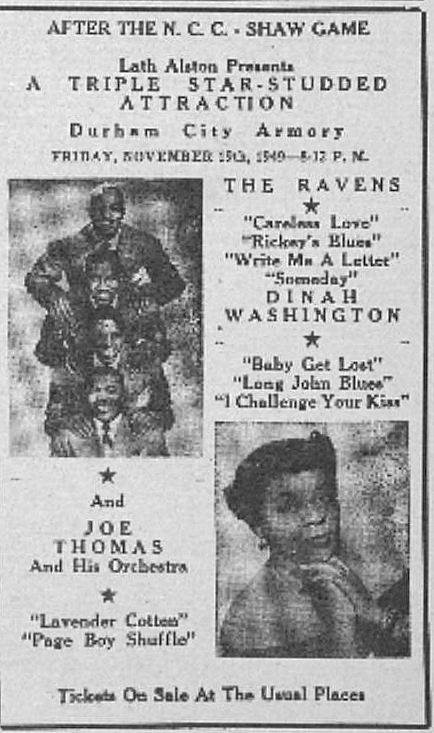

While in New York, Washington got to meet her idol, Ella Fitzgerald (yesssssss!), and became friends with another vocalist who shares her surname and home state, Dinah Washington.

Washington married reed man Julian Dash in 1948. In 1952, she and Dash returned to Birmingham and she focused on raising her children. In the 1980s, after her children were grown and Dash had passed away, Washington began singing again, becoming a regular performer at Grundy’s Music Room.

LUCY “LU” ELLIOTT (recording 1951)

During high school, Elliott was a tuba player who, at some point, and transitioned to being a vocalist and tuba player. As a teen, she won the Amateur Night at the Apollo Theater, which got the attention of someone important, because by September of 1949 she was recording with Duke Ellington. She left Ellington’s orchestra in February 1950 and turned back up singing with the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra in 1951. She recorded two songs with the Hawkins Orchestra on December 6, 1951, “Lost Time” and “I Remember My Love.”

Jet Magazine was covering Elliott, noting that she was the only woman tuba player in the musicians union in 1954.

She had a contract and several recording sessions in the 1960s with ABC Paramount. In 1967, she toured with B.B. King, then spend 10 weeks in Australia performing, then recorded an album called Way Out From Down Under, living the dream and feeding a kangaroo on her album cover.

In the 1970s, Elliott continued touring and performing in clubs in New York, New Jersey, The Virgin Islands, St. Thomas, then made her way to Las Vegas to perform with Redd Foxx. She continued performing in New York and Las Vegas almost until she passed away in 1987.

Her sister, Billie Lee, was also a professional vocalist, but I was not able to locate any details online because she shares a name with a reality TV star. Womp womp.

DELLA REESE (1953)

Born Deloreese Patricia Early in Detroit, Reese started singing for her family by imitating movie stars and by the age of 6 had joined her church’s choir. When Reese was 13, Mahalia Jackson was touring with a stop in Detroit and she heard Reese sing in church. She immediately went on tour with Jackson and joined her tour for 5 consecutive summers.

In 1947 she enrolled in Wayne State University as a psychology major and sang in a gospel group called The Meditations. In 1949, at the encouragement of her pastor to pursue more professional singing gigs, Reese took a job at a bowling alley/nightclub as a host and vocalist.

In 1951, Reese was named Detroit’s favorite vocalist in a newspaper poll, which got her a week-long gig at the Flame Show Bar, where the big names in jazz performed. This started a two year period of regular gigs for Reese at the Flame. While at the Flame, she caught the attention of Lee Magid, a New York agent, who convinced her to move to New York in 1953 and found her a placement with the Erskine Hawkins Orchestra.

Unfortunately, her time with the Orchestra was short-lived and she left after less than a year to advance her solo career. Fortunately, this totally worked out for her because her first recordings were hits – “I’ve Got My Love To Keep Me Warm, ” “Time After Time” and “In The Still Of The Night,” sold 500,000 copies. In 1957, her recording of “And That Reminds Me Of You” went gold, selling millions of copies. In 1959, she signed with RCA and had her biggest hit, “Don’t You Know,” which garnered Reese a Grammy nomination.

In the 1960s she had over 300 television appearances, 100 of those just on the Ed Sullivan Show. She was the first woman to substitute-host for Johnny Carson on The Tonight Show. She appeared in night clubs in Las Vegas and all over the U.S. By the end of the decade, however, Reese felt like she needed to pivot to keep working, so she turned to acting.

Reese’s acting debut came in 1968, appearing as a disco owner on The Mod Squad. This, along with the success of her hosting The Tonight Show, led to Reese getting her own talk show in 1969 called simply Della. She was the first black woman to host her own television talk show, which ran for two seasons.

In the early 1970s she picked up touring again, hitting all the hot spot night clubs in the U.S. and toured Europe, Asia, and South America. On Sanford and Son, Redd Foxx starting referring to Reese and Lena Horne on the show as the ultimate black super stars, so of course Reese made a few cameos on the show. She guest starred in other TV shows, did a few pilots, landed a role in the show Chico and the Man in 1976, and finished out the final season of Welcome Back Kotter as a substitute teacher in 1978.

Reese went on in the same can’t-stop-won’t-stop into the 1980s and 1990s – she recorded albums, was nominated for another Grammy in 1987, became an ordained minister, appeared in the film Harlem Nights with Eddie Murphey, starred in a cabaret revue called Some of My Best Friends Are the Blues, she was the literal angel in the TV show Touched by an Angel, was nominated for another Grammy in 1999, added festivals and symphony appearances to her regular performance venues, just crushing everything always. She was the last of the Hawkins vocalists (that I was able to find) to go – she made it to 2017, ending an era.

SOURCES

Erskine Hawkins Orchestra generally 1 2 3 4 5, Billy Daniels 1 2 3 4, Merle Turner 1 2, Ruby Hill 1 2 3, Dolores Brown 1, Ida James 1 2, Effie Smith 1, Ace Harris 1 2 3 4, Carol Tucker 1 2 3, Ruth Christian 1, Laura Washington 1 2 3, Lu Elliott 1, Della Reese 1 2